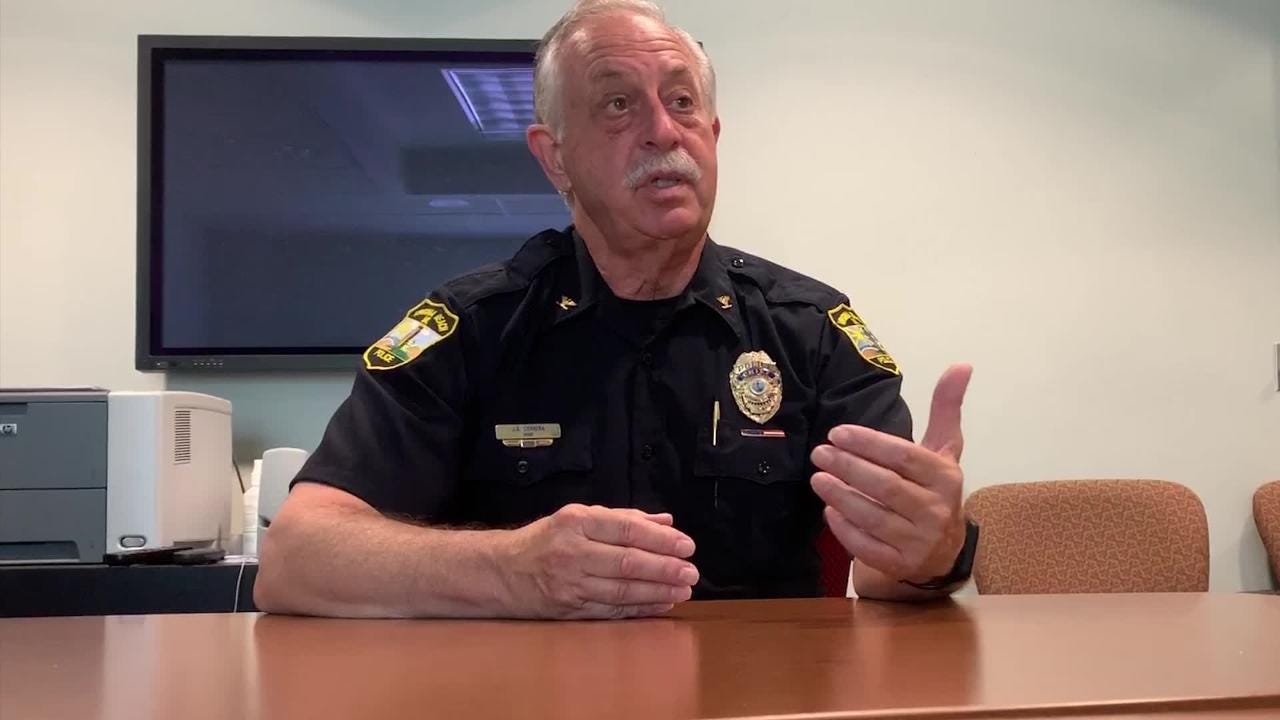

How cops cope with shooting trauma: 'They’re going to be forever changed,' Virginia Beach police chief says

VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. – Officers scouted each office and closet, looking for survivors, opening doors to find scared government workers praying they would survive.

Footage from the rescues shows law enforcers guiding petrified employees down a stairwell where one person lay dead. "Look me in the eye, I’ll help you down,” they said. “Don’t look down, look at me. Focus on me.”

The heroism and compassion shown by his officers in those chaotic moments stayed with Virginia Beach Police Chief Jim Cervera, who described some of the body camera footage in an interview with USA TODAY.

Cervera said police work naturally takes an emotional toll. “It’s the death by 1,000 cuts. It’s the water torture, drip by drip. It eventually has a toll on who you are as a person," he said.

But "to walk into a scene like this, it has an instantaneous effect on you.”

Start the day smarter: Get USA TODAY's Daily Briefing in your inbox

More: Virginia Beach shooting: What we know about the motive, the victims

Cervera said he’s worried about how his officers will cope with the trauma from Friday’s shooting, the aftermath of which he described as a “war zone.” He knows many of his officers will continue to reel from the effects of the shooting as time passes.

“They’re going to be forever changed,” he said.

Departments across the country have faced a similar issue: How do you help officers who have witnessed the unimaginable and who are then thrust back into a job that tasks them with making life or death decisions daily?

The increasing number of mass shootings in the USA has cast a spotlight on mental health and led some departments to reconcile how they help officers cope emotionally in a profession that has historically applauded strength and hid weakness.

“We’re beginning to really research and ramp up what we call officer resiliency, and that is the psycho-emotional part of the job,” Cervera said. “We never thought about this in policing. As a matter of fact, it was looked down upon.”

The police chief said his department was taking a hard look at how to respond, from offering professional and peer counseling to helping officers get back to their day-to-day lives.

The ‘facade’ of strength

Cervera said he’s talked with several of his officers in the aftermath of the shooting, telling USA TODAY on Sunday that he met with two of the four who were part of an extended gunbattle with the suspect.

The other two officers were having time with their family and “trying to get back to normalcy,” Cervera said.

“The two that I spoke with, they are the consummate professionals. They will always give the outward facade of, you know, stoicism,” he said. “While they’re looking at me, and I’m the chief, ‘Yes, chief, it’s OK. I’m doing fine. I’m doing fine.’ ”

Cervera said he knows that “when the door closes,” the facade fades.

“As much as this individual’s the one who caused his demise, so to speak, as much as this individual indiscriminately killed 12 people, the police officers took a life," he said. "That’s a heck of a thing to be able to look at yourself every morning and say, ‘I took a human life.’ They believe in the sanctity of human life. They really do.”

More: Suspected Virginia Beach shooter used a gun suppressor. Did it make Friday's shooting deadlier?

Talking about mental health within the law enforcement community was taboo for many years, but that culture is slowly changing, said Jeff McGill, co-founder of Blue H.E.L.P., a Massachusetts-based nonprofit group that aims to reduce mental health stigma for law enforcers.

"We talk a lot about how to respond to an active shooter, but we rarely discuss the aftermath and long-term mental health care that officers will need," he said. There is no question that an officer's demeanor changes after responding to something such as Friday's massacre in Virginia Beach, he said.

"To suggest that you're the same officer the next day at work is foolish," he said. Shootings change the tactics officers use, raise awareness and put them "more on edge."

More clinicians that understand law enforcement culture are needed, and departments should boost support systems, both within their department and within officers' families, for employees who respond to shootings, car wrecks and deaths over the length of their career, McGill said.

"It builds up over time, and while it might not affect you right now, these psychological injuries that come along with a law enforcement career are likely to cause problems within your personal or professional life," he said. "We have to be more proactive. We have to."

Still reeling after other shootings

Omar Delgado doesn't like to leave his Florida home. It's the one place he feels safe.

The former Eatonville Police Department officer, who was hailed as a hero after saving lives during the Orlando nightclub shooting in 2016, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder in the aftermath of the attack, which left 49 dead. He doesn't watch the TV news or spend much time on social media anymore, but he knew something bad happened Friday after dozens of texts poured into his phone, asking if he was OK.

More: 'Got to see if anybody else needs help': Virginia Beach shooting hero died trying to save others

"It's like you can never get away from it, never. There are reminders everywhere. Every time there's another mass shooting,” Delgado said. “The worst thing that's ever happened to me, the thing I wish I could just forget and move on from, I’m reminded of basically every single day.”

Delgado said departments across the country need to do more to help officers cope with emotions after seeing the horrors of the job, which don't just happen during mass shootings but on everyday calls.

"You get tired of fighting, and I get it, I really do. That's why you get a lot of first responders who commit suicide," he said. "They can’t control their brain from traveling 100 mph. It’s scary. There needs to more programs out there."

At least 159 officers took their own lives in 2018, outpacing the 145 officers who were killed in the line of duty, according to a study by Blue H.E.L.P.

In 2017, at least 140 officers took their own life, which outpaced the 129 line-of-duty deaths, according to a study by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a philanthropic organization that works for the rights of people with disabilities.

Some departments have made huge leaps forward when it comes to mental health, including in Las Vegas.

Officers who responded to the Route 91 concert shooting, which left 58 people dead in 2017 – the nation's deadliest mass shooting – knew they had an in-depth support system within the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department.

The department houses a Police Employee Assistance Program, which was lauded by the Justice Department in a report this year as the "standard" for how departments should handle counseling for officers.

More: In Virginia Beach, a struggle to return to routine less than 72 hours after tragedy

“The LVMPD spent decades perfecting their process so that when the most harrowing calls came, they had the tools, systems and best responses in place with deployment as their primary focus," the report said. Often, departments offer trauma counseling "in the wake of a critical incident, leaving gaps as the practices catch up to the need."

Officer William Gibbs, manager of the assistance program, said departments need to do more, so they "aren't playing catch-up" when employees need the care.

"You want to get in front of stuff like this," he said, noting peer support programs and counseling are ingrained in the culture of the department, starting when an officer is in training.

After the shooting, there was widespread willingness within the department to seek counseling and talk to someone about what officers witnessed, which is not always the case, Gibbs said. He attributes the success to normalizing self-care within the department and building a strong relationship with employees, who have trust in the program.

"We want to help employees become more resilient throughout their career and even after it when they've retired," Gibbs said. "It's about shifting the culture within law enforcement that talking to someone and getting help is not a sign of weakness."